The Murder of Sarah Elswick

The Murder of Sarah Elswick and Why I Tell It.

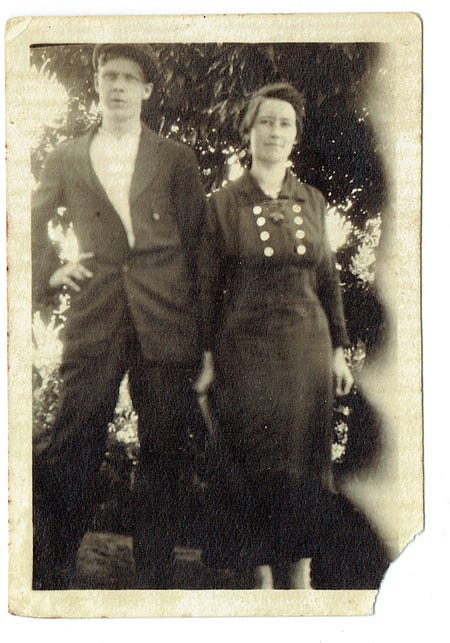

There’s just one grave up in the Smith family cemetery in Southwest Virginia with an image of the departed on it. My aunt Sarah’s photo was printed onto a ceramic medallion recessed into her headstone which says “Asleep in Jesus.” It was only when I noticed this special grave about twenty years ago and asked my grandmother Ann about it that I learned that Sarah had been murdered. No one ever spoke about her violent death when I was growing up in the summers on the mountain...

Press play to hear “Down by the Willow Garden” recorded by myself & Billy Kemp.¹

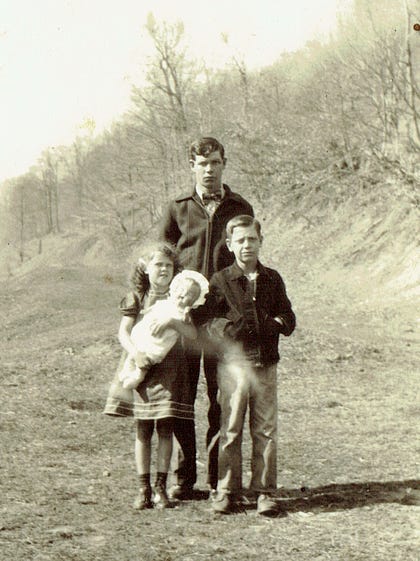

In September 1955, my grandmother, Ann Smith Hankins, was sitting on her front porch in the small coal town of Richlands, Virginia, in the Appalachian Mountains. Ann, along with her seven brothers and sisters had been born and raised on Smith Ridge which bears her great grandmother’s name. She and her husband, Guy, had just come back from their honeymoon and earlier that day they’d gone up to Smith Ridge to attend an all-day meeting and dinner on the ground in the Smith family cemetery. An all-day meeting in our community means a Christian gathering with prayer service, gospel singing, and paying respects to ancestors. Dinner on the ground means a potluck picnic where everyone brings food to share.

As she and Guy sat on their porch in town, a friend stopped by the house to say that an Elswick woman had been shot by a Joyce man up on Smith Ridge. Ann knew that this could mean only one thing: that her Daddy’s sister Sarah Elswick had been shot by Sarah’s brother-in-law Charlie Joyce. This was confirmed by the death certificate. Under “Disease or condition directly leading to death,” it states: “gunshot wound to abdomen.” Just beside “Homicide” and “Home” under “How did the injury occur?” the medical examiner has written: “Patient shot by her brother-in-law.”²

Uncle Charlie seemed to have had no reason for killing Sarah, sister to Charlie’s wife Nannie. They lived next door to each other. My grandmother, Ann, said when a person is mean and that drunk, you just don’t know what they’ll do. Charlie, in the way that people say things in my family, was “hard” on Aunt Nannie – meaning that he threatened and hit her. He would often take to drinking. After the all-day meeting and dinner on the ground, Nannie went home and must have felt something was amiss. Charlie had been drinking at home and was angry. Nannie ran off and hid at the house of family friends. In the meantime, Charlie got drunker and grew angrier at not being able to find Nannie.

Next door, his sister-in-law, Sarah, was preparing supper for her family and was coming up from the cellar of her house with potatoes in her apron. While she was in the cellar, Charlie went across the road, crouched and aimed his rifle through Sarah’s front gate, and shot her as she walked along the side of her house. Later, it came to light that, after he killed Sarah, he spent the night hiding up on the hill above my great-grandfather Avery’s house who was Sarah and Nannie’s brother. Charlie watched the cars, people, ambulances, and police stream by. In the morning, he walked down to a little valley near his house and shot himself. He was found by his son.

As I began to ask more questions about my family history and the names on gravestones, I learned that Sarah’s own father had been murdered in cold blood while serving as Justice of the Peace on the same ridge where Sarah was murdered. My grandfather Kyle’s uncle had been murdered with a car crank by two strangers passing through Jewell Ridge coal camp. The strangers didn’t like him standing up for his sister when they hurled insults at her for fun. The killers drove off and were never found. Alongside these events, there turned out to be many violent and strange deaths in our family’s past in Southwest Virginia.

When Aunt Sarah was murdered on that day in September 1955, she left behind her husband Caleb who shared every grief when their first babies didn’t survive childbirth. Three of their children who survived childbirth couldn’t hear or speak. But one of their girls, Irene, loved country music. She played guitar and sang at talent nights at the coal miner’s union hall.

After the murder, Sarah’s sister, Nannie, and most of her children moved away to Tennessee and other parts of the US which at that time was unusual. Most people, like my own grandmother, lived their entire lives on Smith Ridge or nearby.

My great-grandfather Avery would never set foot in the church that was built across the road from his house because his sister’s murderer, Charlie, was one of its founders.

A passerby might see Charlie’s tombstone which says, “He gave his life for others,” and think he died in a war or was a dedicated civic leader. But, it seems he took his own life so that his children and wife would not have a father and husband in prison for murdering one of their own.

I learned about Sarah’s murder too late to understand every detail and to talk with the people whose lives were devastated by her killing. But I did learn about her death early in my performance and songwriting career. I’ve often thought about how I’ve been drawn to true life and “story” songs since I was a child and this passion has only grown within my own songwriting and traditional repertoire, especially because of the histories I’ve found within my own family.

“Murder Ballads” or violent deaths in the ballad tradition

In the last ten years or so, especially with the proliferation of online debate on social media, there has been significant controversy about the place of traditional murder ballads and songs about violence in the repertoire of old-time performers who are among the primary keepers of the ballad tradition. I think these debates are important because it’s useful to examine why we are drawn to, learn, and share certain songs.

|

I’ve spent the last twenty years or so writing songs, poems, and stories about my family in order to amplify silent voices like Sarah’s. I’ve also celebrated dignity in hard work, spiritual transformation, escape from lightning, and the simple pleasure of gingerbread, among other things. But I am committed to telling our harder stories, too.

I hadn’t yet learned Sarah’s story when I wrote one of my first songs “Back Then.” But I had felt the tension as a child as I witnessed domestic violence, not between my own parents, but between other couples and families on the mountain and in the cities where I grew up. “Back Then” tells of a married couple with a daughter. The song comes from the wife’s perspective. She lives with the scar of a bullet that her husband fired into her side. She’s taken her father’s name again and despite her husband’s “sweet face” which beguiled her “back then,” she knows that prison is the place where her ex belongs. I wrote this song very quickly and unselfconsciously. I hadn’t sat down intending to write a song about domestic violence or a potential homicide – it almost seemed to write itself. As children, we absorb more than we understand.

Had I not asked about Sarah’s photograph on her tombstone, I don’t imagine that I would have ever heard her story because no one volunteered these hard stories to me. I gathered them from a coal mining family whose natural focus had been to move ahead with the sweep of time, neither denying or covering up the past, nor dwelling on or living in it.

My own approach to songwriting is to take into account our family’s legacy of hard truths and violent deaths. If I don’t choose to sing or write about Sarah’s murder and Nannie’s abuse by her husband, I feel my aunts recede into silence, into a place of domestic violence and homicide statistics. If I tell their story well enough, surely no one will think I am promoting violence. But their songs certainly could begin as bluntly as “Little Sadie.”

Went out last night for to take a little round, I met little Sadie and I blowed her down. I got right home and went to bed, a forty-four smokeless under my head. – "Little Sadie" as sung by Clarence Tom Ashley, 1930s

Charlie’s misplaced anger at being unable to control Aunt Nannie could be traded for the lyrics of the traditional song “Rain and Snow.” Some versions of this ballad end in the man killing the woman. Some see this as a song about a woman abusing a man, others see it as a song about a woman keeping a violent partner away from the home. Molly Tuttle re-wrote and re-framed the lyrics to this song to make it clearly about a woman resisting domestic violence. Her version ends with the woman killing the man.

Nudging the lyrics and changing the narrator from a man to woman or the reverse can turn the tables on a ballad and help us to hear it differently. This is Charles and Pete Seeger’s “folk process”. The Seegers noted the process by which folk music developed, by which ordinary people remembered older music and changed it somewhat to fit their needs, sometimes adding new words or new embellishments of the tunes. Cecil Sharp spoke about this folk process too as he collected ballads across the British Isles and Appalachia.

In that spirit of folk process, some people, including myself, collaborate with old ballads such as “Little Sadie” or “The Butcher’s Boy” by writing a new song in reply to the received text. Adrienne Young’s “Sadie’s Song” or my “The Hoot Owl” are examples where the female protagonists find their voice, as in Adrienne’s song, or are given a more substantial back story, as in my song. Years ago, I spoke with Young about her song and we agreed that in our “reply” songs we sought to round out the raw tales of these women – to ask “what if ” on their behalf and before their deaths.

It’s often said that “Sadie” or “Pretty Polly” could have been based on real women. So could the moonshiner “Darlin’ Cora (Corey)” and the nameless pregnant girl in “The Butcher’s Boy.” It’s well established that ballads once served as the news of the day or certainly memorialized that news. Some were salacious, some were warnings, and some recounted actual murders like Aunt Sarah’s. Even if Sadie was a character in a made-up song, her death certainly mirrored reality – a reality which is as relevant today as it was a hundred years ago. Sarah Everard, was abducted and murdered in London in 2021 for no other reason but the senseless depravity of her killer. When I hear “Little Sadie” – “Sadie” being an old nickname for “Sarah” – I think of Sarah Everard and Sarah Elswick, two Sarah’s born nearly 100 years apart, both dead by violence.

Whether to sing a murder ballad or not, to write one or not, will surely depend on one’s reason for learning, writing, or performing songs altogether. I choose to write songs about my own Appalachian heritage and I choose ballads and traditional tunes which resonate with the songs I write. I was once advised by a Grammy-winning bluegrass producer to change the lyric of my song “Jewell Ridge Coal” to “Blue Ridge Coal” so that it would have more “commercial appeal.” My reply was that I didn’t grow up in the Blue Ridge, but in Jewell Ridge in the Allegheny’s.

In other words, I have to sing what is authentic to my experience and my family’s experience (what I understand of it). This is only one way of deciding on a set-list or a way of creating and sharing music. We all have some sort of internal guide; perhaps we love modal tuning or rousing songs. Perhaps we love a sing-a-long or want to play audience favorites.

Maybe we add a song to our repertoire because it speaks a truth to which we hold fast in our own lives.

I also sing the old ballad “Two Sisters” which is about sororicide, and I know exactly why this song bewitched me and why I added it to my repertoire. Two sisters argue over a man, a dress, or, in my version, nothing at all, and one sister pushes the other in the river. The murdered sister’s body floats down to the miller’s pond only to be collected and made into a fiddle by the miller. “But the only song that fiddle would play was ‘Oh the wind and rain,’ yes the only song that fiddle would play was ‘Cry the dreadful wind and rain.’”

What the fiddle cries perfectly encompasses the importance of telling what’s happened and never letting the truth lie behind a quiet looking face on a grey tombstone. Sarah Elswick’s blood flows through me and it’s up to me to say and sing that I once had an Aunt Sarah. She was murdered in cold blood by her brother-in-law for no reason at all. She is remembered.

Thank you for remembering Sarah by reading and hearing her story.

Your friend,

Jeni

Notes:

I’ve mentioned many of my own songs and songs by others in this letter. All of the song titles have links embedded in them if you’d like to hear them. My music is on Spotify, iTunes, and most of the usual streaming services, so if you’re really keen you could create a playlist based on this letter which would be very interesting. I’m not a streamer or I would create one myself.

I have often used “Little Sadie” as a reference in this article because “Sadie” is short for “Sarah” and because it’s a ballad that is often performed, so hopefully one that will be familiar as a reference in my discussion. I could have chosen any number of ballads. You can hear a version of “Little Sadie” sung by Clarence Tom Ashley by following this link. Ashley’s accent is very like home, so that’s why I’ve chosen his version.

You can read an in-depth analysis of the origins of the song “Little Sadie”online at Sing Out.

A version of this letter first appeared as an article in OLD TIME NEWSNo.118 Autumn 2024. OTN is the publishing arm of the Friends of American Old-Time Music and Dance located in Britain. This was my second article for them and I have another forthcoming. If you’re interested in the roots of American Old-Time music and the intertwining of the British and Irish ballad traditions with Appalachian music, this is a great magazine to read and a great group of people with whom to enjoy music.

Billy Kemp and I recorded this traditional ballad sometime before 2016. I’m playing guitar and he’s playing mandolin. This song is also known by the name of the murdered girl, Rose Connolly. It’s a particularly Appalachian ballad and I was drawn to it because a willow tree figured prominently in my childhood at Mawmaw’s. The murderer kills Rose in three ways and then hangs for his crime. There’s an element of the song which suggests his father has persuaded the killer to murder Rose and that adds a layer of strangeness and reveals a lot about parenting gone amiss. New Song Club Members (aka Paid Subscribers) will receive a link to download this song.

A month or so ago, I received an e-mail from the wife of one of my late relatives. She let me know that a couple of family members who I was told had probably passed away were very much alive. Many of the things I’ve learned about my family, I learned from my grandmother and her sisters. They didn’t always know the outcome of things, they lost touch with people over the years, or they never were that close (mainly because of geography) to certain branches of the family. But, some things are written in records and Sarah Elswick’s death is one of them. Her husband had to sign her death certificate.

I’m always grateful to hear more of the story – the parts that perhaps my immediate family didn’t know or mis-remembered. Please get in touch.

Other places you can find me on the web:

Tip Jar at Paypal or Ko-Fi. Thank you for supporting the new song, dolly rescue, bear rehabilitation, and loom re-stringing society!

Substack Notes where I post pictures and thoughts plus excerpts from other writers whose work I’m enjoying.

My shop where you can buy real albums that you can hold in your hand. Albums for the USA and Canada ship from the USA. Albums for the UK and Europe ship from the UK. Everywhere else, please write to me first! What chaos, the tariffs!

My website. And my tour page with dates currently being added.

Instagram and Facebook where I post my adventures almost daily.

My articles for Modern Daily Knitting.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment! The lovely moderator will attend to it gently and promptly.