Scarcity Stitch

A quick note: If you are reading this letter in your email program, Substack may have cut off the ending because there is a maximum length for email and my photos stretch this limit. If you’d like to see all of the photos and read my complete letter, please do click the heart button and you will be whisked off to Substack to finish the letter.

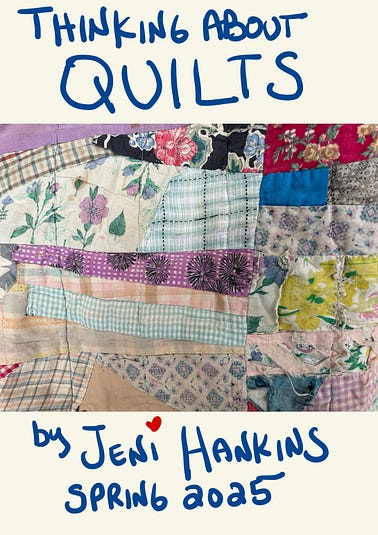

*Please see the end of this letter to download my brand new free zine:

Thinking About Quilts*

In memory of my grandmother, Mawmaw Ann Smith Hankins Shreve.

April 23, 1933 – April 4, 2025

When my grandmother Mawmaw Shreve re-married in 1971, she wore a polyester mini-dress with long lace sleeves. She said that was the style then: “Dresses came down to just below where your fingertips touched your thigh.” Mawmaw, our Appalachian name for grandmother, was a divorced single mother working in the accounting office at the Sears Roebuck catalog store in Richlands, Virginia. Each day in the late sixties, she dressed stylishly for work in maxi skirts and dresses which matched her earrings, bracelets, and necklaces. But styles changed and she cut the bottoms off all of her skirts and dresses to make them into minis. Then she made her dress scraps into a quilt.

I am now the keeper of that quilt. Recently, I asked Mawmaw Shreve if she had thought about throwing away her off-cuts and she exclaimed, “You wouldn’t dare!” I knew what she would say, but I wanted to hear her say it. I didn’t want to project an ideal of thrifty Appalachians onto my own grandmother. But I knew the thrifty mentality that she passed down to me was learned from her own mother, Narcie Smith.

Mawmaw Shreve was born in 1933 just after the Great Depression into a family of seven children. She was in the middle with siblings to mind her and little ones for her to mind. Narcie and Avery, her parents, lived like many Appalachian wilderness families in a house they built themselves high up on a mountain ridge. Avery worked in the coal mines and kept bees. Narcie cooked, kept house, grew most of their food on a steep hillside, milked the cow, made butter, and washed their clothes and linens on Mondays in washtubs on a wash board.

Narcie sewed clothes and quilts on her Singer treadle sewing machine in a corner of her bedroom. Everyone in her family had only a few items of clothing and the girls would trade dresses, tops, and skirts with their neighboring cousins. She made underclothes from bleached “chop sacks” which had held feed for hogs and she made dresses from printed flour sacks. A store bought dress or store bought material was a luxury and a treasured possession. The men had store bought suits and collared shirts which they kept carefully and Narcie mended carefully.

Back when Narcie was twelve years old, she’d foraged enough bloodroot or “percoon” as she called it – a skill learned from her half-Cherokee mother – to sell in town. She used the money to buy new material for her own dress. Narcie knew the value of cloth.

Because she prized cloth, Narcie saved it. No scrap was too small or the wrong kind. Anything too small to make a garment she kept near her sewing machine to be saved for quilts. My dad, who grew up with Narcie in their multi-generational home, remembers being laden with quilts in the winter. He said that when he went to the dentist and they put the lead blanket across his chest, he decided that’s what sleeping under all of Narcie’s quilts was like. He didn’t move an inch from the time he went to sleep until morning.

Narcie’s quilts involved inventing and improvising the overall quilt pattern as she pieced. The quilt took the form of the patches she had and, as her daughter said, “If you look close, they were none too straight.” If she had enough fabric, Narcie often chose a nine patch, log cabin, or spider web block because they were the most adaptable and could be fashioned out of many differently sized bits. Sometimes she would place a few nine-patch blocks amid a collection of odd sized pieces.

Narcie combined corduroy, cotton, wool, rayon, burlap, silk, and, eventually, polyester into her improvisational quilts. Mawmaw says, “If it wasn’t attached to something else, Mama put it in a quilt. One time I came home to find her and Elsie Brown putting an old tablecloth your mom and dad gave me into the middle of a quilt. Nothing was safe!”

At the same time that my great-grandmother was patching together every scrap of spare fabric in whatever pattern made sense given her materials, the women of Gee’s Bend in Alabama were creating their own language of quilt patterns based on what they had to hand. They, too, were lead by the fabric into innovative constructions and into combining atypical fabrics.1 Two very different cultures, one predominantly white Scottish, English, and Irish, and the other, black with African roots, both made the cloth work for them. And they both had to because there was simply no other option.

|

We can look further afield than rural America to make connections with people and traditions where cloth was also never abandoned just because it could no longer perform its original purpose. In the Bengal tradition, there’s kanthawhere layers of discarded clothing, mainly saris, are layered together using narrow rows of running stitch. “Kantha may owe its name to kontha, the Sanskrit word for rags.”2 Though these quilts and their many Western reproductions have become wildly popular in recent years, this is a deeply ancient tradition mentioned in fifteenth century Bengali poetry. Five hundred years later, the agile fingers of women still ply needle and thread to transform disparate and weaker cloth into strong multicolored coverings.

Even further to the east, in Japan, from at least the early 19th century needle crafters worked sashiko, seed, and running stitches into cloth made of cotton and hemp dyed with indigo as well as cloth made of linden bark waterproofed with persimmon tannin. These stitches preserved garments, futon covers, floor covers, sacks, curtains, and many other household textiles. These mended Japanese textiles are called boro, shortened from boroboro – boroboro meaning something tattered or repaired.

In the summer of 2023 the Brunei Gallery in London held an exhibition of Japanese recycling in fabric, paper, and pottery featuring boro textiles. The curators were anxious for visitors to remember that peasant hands had made these recycled cloths out of need.

“[Although] these textiles pieces have become very popular with collectors in Japan & throughout the world over the last 20 years [and] are often marketed as 'abstract art' in the Western context, [t]hey are in fact an important aspect of Japanese history and culture, showing the resilience and creativity shown by working people living in a very harsh environment with very few resources.”3

This truth about the real life poverty which necessitated the practice of boro can also be said about Bengali kantha, Gee’s Bend quilts, and my own great-grandmother’s quilts in Appalachia. The reason to stitch, patch, and repair these objects was to extend their life because there were no affordable alternatives available. The Brunei Gallery curators also spotlighted the word mottainai which “denotes a sense of regret when something is wasted, its usefulness and value not fully realized.”

If there was one overall sensibility that I’ve inherited from my Appalachian family it is this concept of mottainai that comes from a country all the way across the world.

Mawmaw summed it up in a different way when she said, “You wouldn’t dare!” when explaining why she felt compelled to take the cut-off hems of her long dresses and make them into a quilt. You wouldn’t dare just discard them.

I call this respect for materials and the ability to transform them “Scarcity Stitch” – making something durable and essential out of what others might consider disposable. Scarcity stitch is practiced in traditions where there is an urgency about extending the life of cloth. In Japan, in Bengali culture, in Alabama, and Southwest Virginia, in times of economic depression, in caste systems, in socially marginalized communities, in war, in geographically and economically isolated communities there is inherent scarcity – scarcity of materials and little or no money to buy materials. What you have around you, even if it is used and tattered, is your greatest resource.

|

As a global community we are facing an approaching wave of scarcity – scarcity that many have always known. Climate change causing weather extremes and magnifying natural disasters throws even the wealthiest societies into disarray. Food, water, and environmental poverty may soon affect us all. One way we can turn the tide of this wave is by reducing our consumption of cloth. Water, chemical dyes, commercial crops, and modern slavery combine to meet the global demand for cloth. Yet, there are mountains of cloth abandoned in African deserts and reefs of micro plastics forming in our seas. We are contributing to climate disaster because we can not stem the demand for more new cloth.4

Some actors in the cloth trade are swimming against this tide including major retailers with buy-back and mending schemes, fiber recycling innovators,5 and teachers of mending skills. But these remedies are, in fact, a drop in the ocean compared to the new cloth generated every single day. So much of the cloth used by our ancestors was biodegradable. It was plant or animal based and would eventually decompose. Now, we are also amassing canyons of petrochemical textiles with no global plan for managing them.

Though many of us reading here may not know the level of scarcity that my great-grandmother or the Gee’s Bend quilters knew, we are experiencing a new environmental scarcity and it means our relationship with cloth needs to change. The more we can re-use, re-imagine, re-cycle, and re-fashion fibers, the more impact our needles will have. We can mend the planet one stitch, one saved scrap at at time.

Narcie Smith made quilts because the scrap materials she had were a ready resource and those scraps covered her large family in warmth. She had a treadle sewing machine. She found time to sew in the evenings. She and her best friend, Elsie Brown, would lay their quilts out on the bed and tack the layers together, and Narcie would stitch the binding. Narcie’s Appalachian childhood gave her an innate understanding of the value of cloth. Long after her children and grandchildren were grown and she had all the blankets she could want, she still set aside scraps for quilts.

After Narcie passed away, Mawmaw and I found a bundle of table scarves and aprons in her window box seat. Each one had been hand embroidered with flowers or birds and used until there was a hole, small stain, or the binding had come loose. Mawmaw and I agreed that this precious bundle of material was one more of Narcie’s quilts waiting to be made just in case anyone should need one. I’m now making that quilt because I know my great-grandmother wouldn’t want her cloth to go to waste —because she taught me the price of cloth.

If you’ve enjoyed this letter, please touch the heart, leave a comment, restack or share. You will be letting other readers know that you think there’s something good in here.

Thank you!

And thank you for spending this time with my grandmothers and me.

Your friend and fellow maker,

Jeni

Note: I have given names to Narcie and Mawmaw Shreve’s quilts in order to make them more easily distinguishable from each other and to aid in discussion.

1 “Gee’s Bend.” Gee's Bend | Souls Grown Deep. https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/gees-bend-quiltmakers. Accessed October 9, 2023.

2 Sunder, Kalpana. “The stories hidden in the ancient Indian craft of kantha.” The Collection. BBC Global News Ltd. 20 October 2022. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20221020-the-stories-hidden-in-the-ancient-indian-craft-of-kantha?ocid=ww.social.link.email

3 Japanese Aesthetics of Recycling, 13 July - 23 Sep. 2023. Brunei Gallery, SOAS, London.

4 Dube, Shailja. Interview. “The World at One, September 4, 2023.” The World at One. BBC Radio 4. Hosted by Sarah Montague. 4 September 2023. Radio.

5 Parkinson, John. Interview. “Shoddy: The Once & Future King.” Haptic and Hue. Episode 24. Hosted by Jo Andrews. https://hapticandhue.com/shoddy/

I have made a free PDF booklet about nine-patch quilts inspired by the way that my great-grandmother Narcie Smith made hers. I will follow this up with a step-by-step YouTube video later in 2025. I have filmed it, but the editing will take time.

With tremendous thanks to my colleagues at Modern Daily Knittingwho published the abridged version of this article. You can read all of my writing for MDK here.

As I prepared this article for publication, I sat with Mawmaw Shreve. She fainted due to an infection back in January and this lead to stays in three hospitals and two nursing homes. She caught flu, another infection, and pneumonia. I was with her through most of March and early April, decorating the wall of her nursing home room with cards. Thank you for sending those cards. I read excerpts of this letter and Thinking About Quilts to her. She could hardly believe that Narcie’s quilts and her own were something worth noting. Mawmaw passed away on the 4th of April just nineteen days shy of her ninety-second birthday. One of the last things she said to me was, “Honey, I’ll tell you any story you want to know.” And she always did. This story of Narcie’s quilts exists because Mawmaw told it to me. Thank you, Mawmaw.

Recently, I wrote a song about my great-grandmother and her quilts called “The Power in the Blood” which you can read about and hear. I also wrote a song based on The Quiltersthe exceptional book of oral histories of women in West Texas. My song is called “Windmill.”

Some of what I say in this letter, I speak about in an earlier article which also includes thoughts about Jane Austen. You can read it here.

Other places you can find me on the web!

Substack Notes where I post pictures and thoughts plus excerpts from other writers whose work I’m enjoying.

My shop where you can buy real albums that you can hold in your hand.

My website.

Instagram and Facebook where I post my adventures almost daily.

My articles for Modern Daily Knitting.

New here? You can read a brief history of me:

here.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment! The lovely moderator will attend to it gently and promptly.