Virginia Woolf & Thanksgiving Dinner

Virginia Woolf & Thanksgiving Dinner

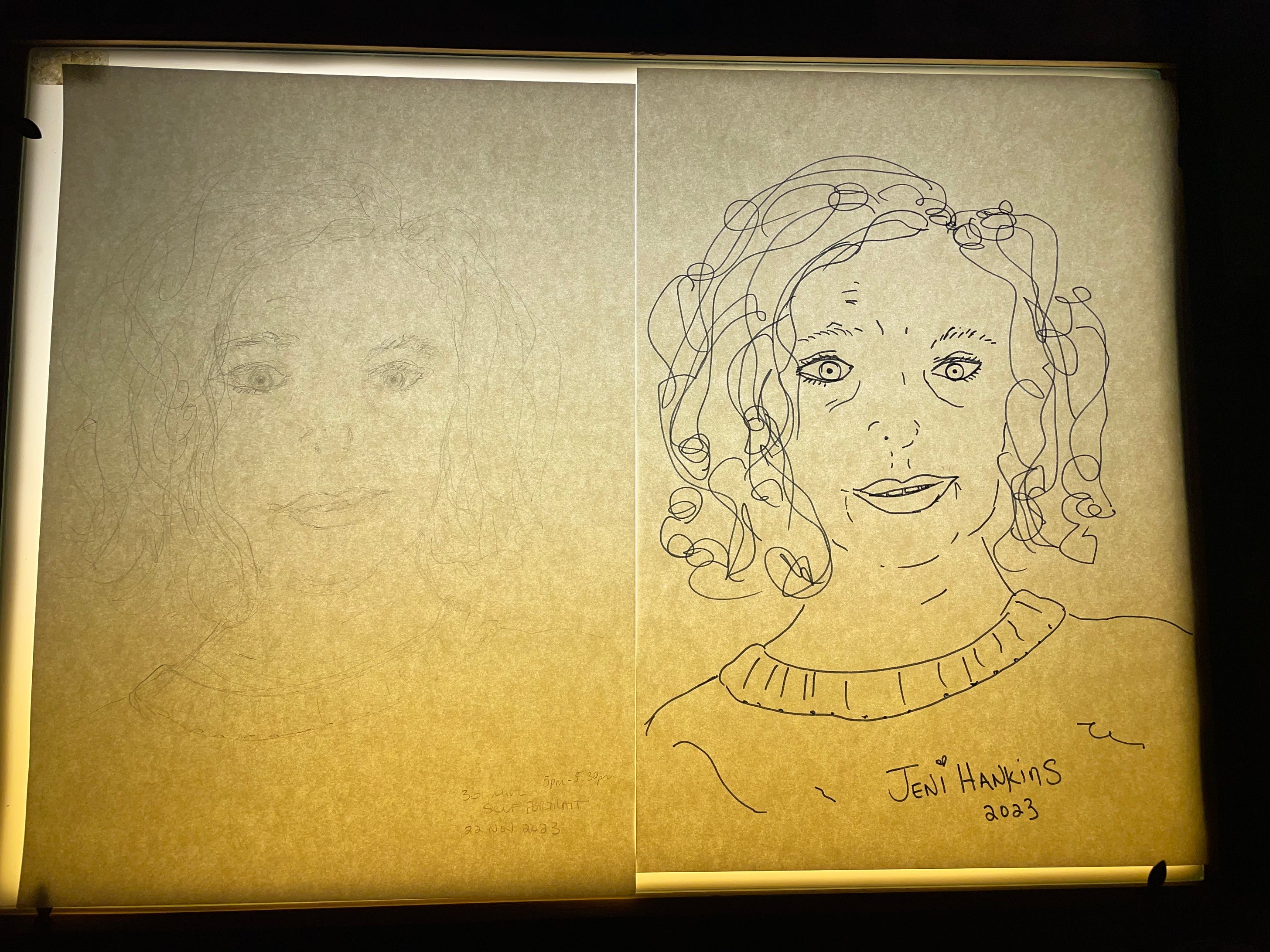

Self portrait with a Brown-n-Serve dinner roll.

This past week, I saw the Wellcome Collection exhibition here in London on The Cult of Beauty. One of the galleries focussed on mirrors. Sometimes, it’s easy to forget the obvious like there weren’t proper mirrors to reflect our faces until fairly recently in human history. “It was not until the 14th century with the invention of glass-blowing that undistorted mirrors became available, and then only to the wealthy.”¹ The photo below is my reflection in an Egyptian bronze mirror from more than 2000 years ago.

Two other things happened this week which made me think about how we see ourselves and why the holidays can be a heightened time of seeing and reflection.

Last week, an old friend sent me a “Happy Thanksgiving” text with photos of his family’s pumpkin pies and the kids gathered around the kid’s table. We had a little table like this for huge family holiday meals at Mawmaw’s house in Southwest Virginia. (I shared a photo of this table in a recent letter to you). I’m sitting with the love of my life, my cousin Rachel, and my cousin Shad who wasn’t used to our loud family gatherings because he lived in Florida. I simply wanted to grow up to be Rachel. She was two years older than me. Everyone says now that I couldn’t order at Wendy’s without saying, “What’s Rachel having?”

When I looked at the photos of my old friend’s Thanksgiving, I thought how strange it was – like a ritual from a clan to which I once belonged which I was seeing from an island where I now drink tea and eat biscuits (biscuits that aren’t my childhood biscuits of the American South, but actually cookies). I haven’t celebrated American Thanksgiving since I moved to England seven years ago. My friend’s greeting and photos sent me at warp speed back into memories of all of the anxiety and apprehension, but also excitement I felt about the holidays of the past.

My distance from celebrating Thanksgiving and big holiday gatherings in the USA means that they do feel like something from a far-away time and, so, I’m able to see them with a sliver of perspective like the old photos of myself where I thought I looked awful and now I realize I looked completely fine.

And that is actually the thing about holiday gatherings – looking. How I looked. How I felt about how I looked. What other people would think about how I looked. And, most importantly, what they would say. Because our family is full of people who have no problem saying, “Oh, honey you look good with a little weight on you.” Or “I don’t know why you don’t dye your hair.” Or “Don’t you think you’d be more comfortable in that other dress?”

Because, after all, when you haven’t seen someone for a whole year, one of the first things that’s going to strike them is how different you lookcompared to the the last time they saw you. This was especially true in the days before social media when your grandmother would get that one really wonky school portrait each year rather than a running photo montage of everything in your life. Very few of my relatives would know about my inner life or my daily victories or defeats from one year to the next. They wouldn’t know that I’d won the Pulitzer Prize (I haven’t, but hypothetically speaking) unless I wore a badge saying, “I know my hair is flat and my dress is wrinkled, but I won a big fancy award for that book I based on all of these crazy family gatherings.” They would just wonder why I didn’t use some curlers and an iron that morning.

These Thanksgiving thoughts about family holiday gatherings and looking at and being looked at by family rubbed up against a project I’ve been working on for the last month – a stitched self-portrait.

The textile, natural dye artist, and writer, India Flint, has asked fellow stitchers to send self-portraits to Australia to celebrate the re-opening of Fabrik Arts in 2024. I decided I’d enjoy the challenge of “drawing” myself in stitches and got started.

In my enthusiasm, I read India’s instructions hurriedly and first stitched a portrait using my sewing machine and an embroidery hoop. Then, I realized the work was meant to be hand-stitched, so I prepared a handkerchief for hand stitching. I traced both of these portraits from a watercolor painting and crayon drawing I made of myself last year. But I started adding a lot of other portraits of my family around my head on the fabric because I feel like they are around me all of the time. I’m always thinking of myself in communion with them and acknowledging their imprint on me.

The second portrait became too unwieldy because I’d made it so layered and I worried it would take a long time to stitch and I was worried about the deadline. So, I decided to sit in front of a mirror with a fresh piece of paper and draw myself again.

Have you tried to draw your own portrait? It’s a very strange and enlightening act. First of all, I found myself feeling how seriously in the present I was. I mean there’s hardly anything more present than looking at myself and then looking at the paper and trying to make marks that translate the human in the mirror into lines. I can’t think about anything else or do anything else. I’m literally fully in it. There’s a constant confusion between looking and drawing. I think with self-portraits, speaking for myself, I’ll never be able to really “capture” my image. It’s not about drawing ability or reality, but about the trick of translating malleable round humanness onto flat paper with a stick implement or brush. I felt like I was chasing my reflection.

But I got something on the paper and then I needed to reduce the pencil lines of the original drawing into more of a contour drawing to make it a reasonable guide for embroidery. I did this using a flair pen (my favorite kind of pen ever) and a light box and another piece of paper. Then, I put my fabric over the flair pen drawing and traced that. Even though I taped the fabric down, it moved, as fabric will, and it was hard to see what I’d already traced unless I turned the light off and on.

Finally, I began embroidering the flair pen lines with three types of black cotton thread – soft cotton matt sashiko thread from Japan, slightly shiny Anchor embroidery thread from England, and very shiny twisted Anchor perle thread also from England. It turns out I don’t have much black thread in my mountain of sewing stuff, so I combined what I had to make different line widths.

With each iteration from pencil, to ink, to thread, my portrait became more abstracted from my actual self. In the end, the image became cartoon-like. I felt like a character from Scooby-Doo or a woman in a Roy Lichtenstein painting.

And this brings me back to big family holiday dinners and the way that our image of ourselves becomes refracted, reflected, and dispersed by all of the spoken and unspoken comments, and the accompanying looks that we absorb when we come up against people who have known us since we were babies (parents) or who we’ve just met (cousin x’s new flame). I feel this has a splitting effect inside me and that I’m probably having this effect on everyone else too.

I think this is possible anytime we see someone that we haven’t seen for a time. Suddenly, at the same time, you are the person that you are now and the person they used to know, and for them it’s the same. In a big family gathering, that’s just amplified.

This doesn’t always have to be bad, but sometimes like loud noises or crowded spaces, it can be disorienting.

One of my favorite ever writers is Virginia Woolf because as an undergrad I took an entire course on her novels at the University of Galway in Ireland and absolutely loathed them all and felt she was the enemy of reading comprehension. Oh, she was a head-splitting puzzle. And then out of some kind of challenge to myself, I took another course on her novels in grad school and decided she was the best writer on the planet and understood humans like no one else. When you catch your reflection in the re-reading of a novel, you will meet a different you in five years.

In Between the Acts, Woolf tells the story of a community putting together a play. At one point, various actors and scenery-movers are carrying mirrors and one young man can’t carry his any further, so he stops, and then so do all of the other mirror-bearers. The result is that the audience is suddenly confronted with a fragmented reflection of themselves.

Woolf writes:

“It was the cheval glass that proved too heavy. Young Bonthorp for all his muscle couldn’t lug the damned thing about any longer. He stopped. So did they all – hand glasses, tin cans, scraps of scullery glass, harness room glass, and heavily embossed silver mirrors – all stopped. And the audience saw themselves, not whole by any means, but at any rate sitting still.

So, that was her little game! To show us up, as we are, how. All sifted, preened, minced; hands were raised, legs shifted.”

. . . .

Scraps, orts, and fragments, are we, also, that?”

When I see the picture of myself at the children’s table at Mawmaw’s house, or laughing with my Dad at Christmas, or in the iterations of my various self portraits, I know I am in there, but I am always also here just now. I wish I could go back and scoop them up in my arms, including myself, and say hello. Please, don’t worry so much. Your dress is fine and your hair is like a dream. Let me take your picture, Dad, one more time to have for later. Eat all the pie you like.

When you see your sister has changed her hair, or your aunt has become increasingly miniature as she approaches ninety, or your cousin – who was a string bean running through a sprinkler – now has a toddler and a baby on her hip, they will see themselves in the mirror of your eye. Let it be a kind mirror. And, if it’s true, let them know how much you loved wearing their lipstick when you were a kid or how you always thought they were the best at Monopoly. Because in another year or in another second, the reflection will shift, and some people will step outside the frame and others will step in. Now is our chance to get it down on paper as best we can. Now is our chance to gently brush the stray curl from a forehead.

As Woolf’s character Rev. G. W. Streatfield says of the play: “To me at least it was indicated that we are members one of another. Each is part of the whole.”²

In South Africa: Umntu ngumntu ngabantu. A person is a person through other persons.³

I’m wishing you love and kindness in the coming weeks and always.

Peace and blessings be.

Your friend,

Jeni

Wellcome Collection curatorial descriptions. The Cult of Beauty.

Virginia Woolf. Between the Acts. First published in 1941 just after her death. The original cover includes artwork by Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell.

I learned this expression at the stunning photo-documentary exhibtion unbuntu: I am because we are by Andre Francois at the Brazilian Embassy in London (NOV 2023).

|

In January of 2023, I started offering paid subscriptions to my newsletter because I felt that if people actually subscribed it would give me a push to commit to writing every month this year. And I thought that commitment to telling stories would be very good for me. Because I’ve had paid subscribers and founding members over this past year (THANK YOU!), I’ve written two letters each month rather than the occasional one that I wrote from time to time over the last few years. This has been very special for me as a writer and I am so grateful to everyone who reads these letters and goes on the journey of each story with me.

So, I’d like to see where this could go next year and it’s been suggested to me that adding a song element would be welcome. So, in 2024, I would write one letter/essay each month AND share a new song along with its story. At the end of the year, I will have twelve songs which is an album-full. I’ve put this poll here in case you’d like to chime in on this idea. It holds no obligation. You are also welcome to leave a comment with any ideas. Thank you.

|

Find me on:

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment! The lovely moderator will attend to it gently and promptly.