Percoon

“I sold that blood root down in town

to buy my wedding shoes –

high-top boots for riding Nelly and dancing all night with you.” – “Milk and Butter” by Jeni Hankins from the album I Fell Into the Fire

Listen here.

Bloodroot. “Percoon.” I only discovered its name and what it looked like by chance and that’s when I learned what it meant to my great-grandmother.

This past summer, while I was home in Southwest Virginia, I looked for the bloodroot where I’d found it four years ago. Back in 2019, I saw this unusual looking plant on its spindly stem while I was collecting some iris bulbs from Mawmaw (my grandmother). The leaf was shaped like a hand or the antlers of a moose to me and it had wrinkles on the surface like the lines in the palms of our hands. I asked Mawmaw if she knew what it was and she said, “Of course, that’s bloodroot. Mama sold that down in town and bought the material for her first dress she sewed.”

Statements like this just fall out of my grandmother’s mouth casually, but to me they thunder into my songwriting and storytelling brain with a great furore. I just want to sit down with a pen and immediately think out a whole novel or short story built around this little bit of family history. For now, this little revelation has found a role in a verse my song based on my great-grandmother Narcie Smith’s early life selling milk and butter from horseback with her big brother Pat.

|

“Percoon” is what Narcie called bloodroot, according to Mawmaw, and that fits because the Native American Powhatan (Virginian tribe) word for bloodroot is “puccoon” – a word that Narcie would have learned from her half-Cherokee mother, Sarah Nipper. Native Americans valued bloodroot for its fingerlike rhizome which gives an orange dye. The dye was used for painting skin and for dyeing basket-making materials. Bloodroot was also used as a poison because it’s highly toxic. In small quantities, it works as an emetic (makes you vomit), but I wouldn’t risk it. It was also combined with beeswax, turpentine and other ingredients by mountain folks to make “black salve” to burn what my grandmother would call a “place” off the skin or draw a splinter out of a finger. I wouldn’t risk that either (and the FDA doesn’t recommend it).

But Narcie’s use for percoon was to sell it for money in town where brokers bought mountain harvests like bloodroot, ginseng, and morel mushrooms to sell on to bigger markets.

Because I spent several months of the pandemic happily experimenting with natural dye, I was excited to see if I could collect enough bloodroot responsibly to do a bit of natural dyeing in Mawmaw’s kitchen. I mordanted my cotton and linen with soy milk. And I turned my large skein of wool into mini-skeins. I put on my foraging clothes, took my machete, trowel, and my basket, and headed into the woods. As my eyes adjusted to all of the greens, browns, and grays, I began to be able to differentiate between plants. I placed my feet carefully – not wanting to step on the very plant that I sought. And then, there they were sprinkled throughout the forest floor.

Bloodroot is “planted” by ants which is called myrmecochory. What a wonderful word from the Greek for ant circular dance! I didn’t know that at the time, but I was eager to look it up later. And I looked it up because, as I was foraging, I noticed that percoon liked the sandy, loamy bits of the forest floor. No hard, compacted, or sodden earth, but places where the native sandstone had eroded and the leaves had sifted themselves into a dry compost. Ants like these places too and handily create their own “sand” in the course of their living habits.

As I began to collect, I learned that the stems of bloodroot are very fragile and that it’s best to use them as pointers and follow them down to where they meet the earth. You won’t get to the root if you pull by the stem, it just breaks off. It’s good to put the trowel about two inches under the base of the stem and lift up. The root will be in your trowel. The roots are like strange hairy creatures and when you shake the earth from them, they look like they could crawl away on their spindly legs. If you break one in half, you see the “blood.” The color is more orange than red, but certainly has that tint of dried blood.

When I was in the forest, I felt blessed to have this chance to forage on private land which once belonged to my ancestors. I thought my great-grandmother would have been proud of my ability to identify this special plant, to collect it deftly, and to preserve plants in each patch for the future health of this forest. And she would have been tickled that it was the story about her that sent me into the woods.

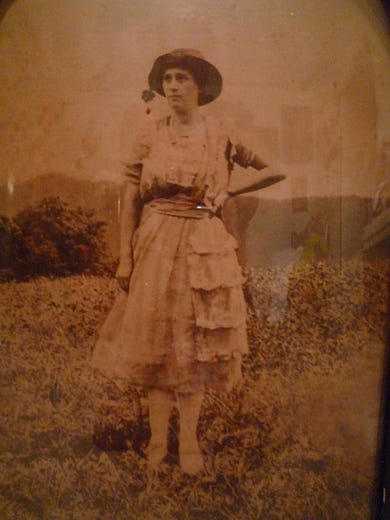

As I was circling back home, I found an outcropping of sandstone and at the base of the stones stood a beautiful patch of bloodroot. This didn’t feel like any normal place to me. It felt like a sign from my great-grandmother, a memorial of a kind. So, I sat there on the ground with my basket beside me and thought about Mawmaw Smith and the fierce abundant love that she gave me. She had a wild sense of humor, she loved to hug big and strong, she wore bright hats and shiny shoes, she suffered no fools, and she cooked everything on high. She made quilts out of any scrap of fabric she could get her hands on and she didn’t care much if the seams were straight or the colors were loud as long as it was warm and colorful. She took no sass, but gave plenty of it when she felt like it.

When she was about twelve years old, she collected enough blood root to trade for money to buy material for her own dress. That was Narcie Smith, my great-grandmother. Born, raised, lived, and crossed over in Appalachia.

Thanks always for reading along.

Your friend,

Jeni

You can hear Narcie speaking a bit about her life on this recording from my album Heart of the Mountain.

Here are the results of my bloodroot dye pots!

|

P.S. This newsletter began all the way back in 2006 as a way to keep in touch with my music fans about upcoming Jeni & Billy concerts and Jeni Hankins concerts. Over the years, I began writing essays about homewhich meant a lot to me since I’m often away from home and these letters found a generous audience in so many of you. With sustained touring still not an option for me because of private health and logistical reasons, this space has become a place to release new songs and continue the stories of Southwest Virginia that I tell in my concerts. Thank you for continuing to be a part of my “show” here online. I will continue to play individual concerts as opportunities arise and circumstances allow.

As always, I’m glad to hear from my friends and fans near and far. If you enjoy these essays, you can give me the gift of time to write by becoming a paid subscriber or making a tip in my interweb tip jar. Your monthly tip costs less than a Kroger Private Selection® Classic Cracker Collection Variety Pack. Some folks who are hesitant about online subscriptions because of cyber-ne’er-do-wells have asked if they can subscribe in other ways like PayPal, check, or direct debit. All is good! It’s $5 (£4 a month) or $55 (£45) for a year. Just write to me at jeniannhankins@gmail.com.

Also! Because I am curious about what you’d like to hear or see or read from me in this place, let me know.

Ok, bye for now!

Find me on:

YouTube and here on YouTube, too

X formerly known as Twitter (not a frequent twitter user, but I am there)

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment! The lovely moderator will attend to it gently and promptly.