Remove Not the Old Landmark

Dear friends,

The cabin fell down.

What is it about old buildings? This morning when I woke up, I asked myself why the collapse of our family cabin matters so much to me when war (not to mention fire and earthquakes) is ripping apart and leveling entire cities right this minute. The National Trust in Britain is the largest conservation charity in Europe. They protect over 600,000 acres of land and 780 miles of coastline. Without them huge swathes of British land and coast would fall into commercial and corporate hands and we the people would never set foot on it again. But their mission started with a woman, with a garden, then five acres of land on a hilltop in Wales, and then a house. A single house. They now look after 500 houses.

The reason they look after houses is because they believe that houses teach history and history is our story and it’s a living story. We can disagree with that history. Challenge it or celebrate it. But if the house stands, then it’s a landmark of a time and space and collective memory. For me the cabin was such a landmark. When I learned about the cabin, I’d been writing songs about our family for about six years and I’d recently released the Jewell Ridge Coal album. From that point on, our family homeplace became a profound physical connection for me to the hands of my ancestors. I could literally see the marks of my great-great-grandfather’s adze in the timbers. I found the kitchen sink that is now in my Nashville house buried in the ground there. I loved to move through the cabin’s two small surviving rooms and go up and down the stairs and feel that real sense of my people having actually been there. It was a pleasure and an inspiration to me.

It’s strange how I never knew about the cabin when I was growing up. It took all of ten minutes to walk there from Mawmaw’s house. It was the old homeplace of the Smiths, but no one ever mentioned it. I’d never even been down that road. When you’re a little child, roads look long and forbidding. Everyone was moving forward and creating their lives. The future was the thing. But because of my writing and my music, I started looking back. I asked questions and scrutinized old photographs. That’s when I learned about the cabin and Mawmaw took me down to see it. That’s when I fell in love with it.

Some years ago, I worked with the gas company to see if I could buy the cabin and a small amount of land around it. The cabin was supposed to have been moved and rebuilt in a safe place many years before by a relative who’d negotiated with the gas company to keep it (but crucially, not the land on which it stood). His plan never came to pass for reasons I don’t know and he became sick and died and then ownership of the cabin reverted to the gas company. Only a couple of years after I learned about the cabin, the company installed the gas well and tanks and they blocked the road to the cabin with debris. Since then, there’s been no way to our homeplace but on foot and no way to keep the path clear except by hand. It’s extraordinary how fast trees can grow. To actually get to the cabin, I had to climb the clay earthen mounds formed when the site was leveled for the gas well. And then I would continue slowly on foot, cutting through brambles and trees, looking for snakes, and keeping an eye out for bears.

Still, the company was very kind in their communication with me and they seemed willing to let me move the cabin if I could now get to it. I wondered if I could bring the timbers up along the land below the electrical lines….

My Dad and I talked through all of this a lot. The expense. The logistics. But it also turned out that the cabin sat exactly on an intersection of land shared by three different coal companies and dozens of heirs. The company with which I was speaking didn’t have the last say in the matter. Everything was a mess – a mountain of obscure leases and companies whose names had changed so many times. A cabin is a big thing to move and bureaucracy is a big thing to move, too. My Dad once said that my history with the cabin began at a time when the work of saving it was bigger than me. He reminded me that I am not the National Trust (nor am I The Barnwood Builders or Maine Cabin Masters).

Then the cabin was vandalized and became more vulnerable. Back in 2018, a contractor for the gas company had been clearing trees, brush, and vegetation along the path of the electrical lines near the cabin and, while they had their chainsaw handy, they cut half a dozen large timbers out of the north side. That discovery was a shock and I did what I could to shore up the damage. It was okay the next year when I returned and okay the year after that when relatives sent me photos from the memorial I created there.

An uninhabited cabin is like a giant heavy ancient Jenga set exposed to wind, rain, falling trees, and termites. All of this natural erosion and the stolen timbers meant the cabin fell down.

A few weeks ago, my sister and I had to cut up through the woods where the trees were tall and the undergrowth was sparse since the old road has now become an impassable wilderness. I thought the cabin looked strange from the woods. Something wasn’t right. Too much tarpaper. Too black. And when we finally passed through the tall weeds, that’s when the wrongness of it was explained.

Now it will go back to dust. There’s nothing in it that cannot return to the earth. The wood. The hinges. The nails. The scraps of newspaper on the wall. The cabin is digging its own grave now.

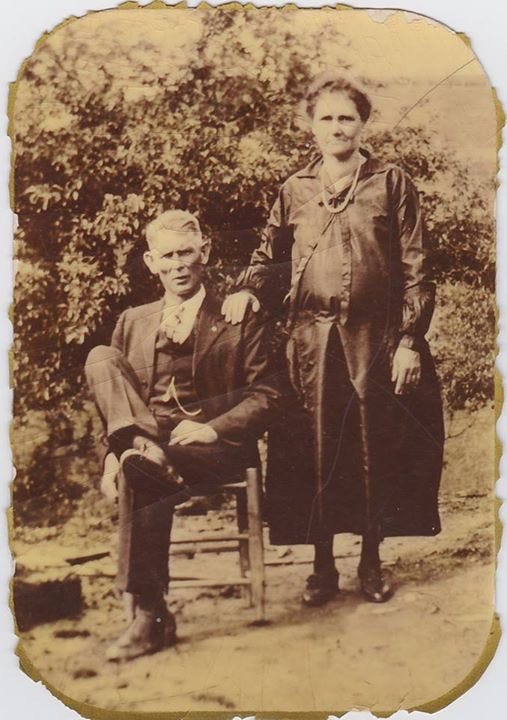

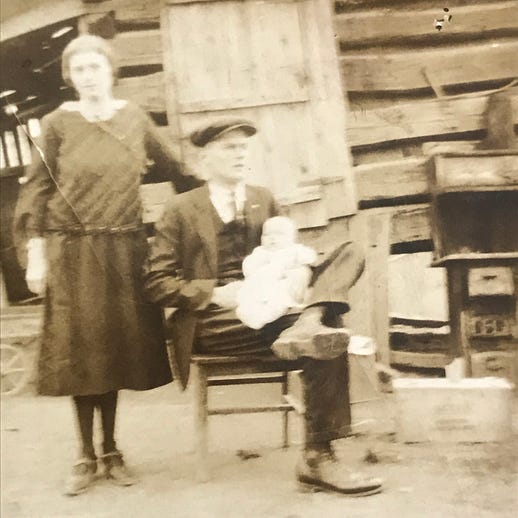

The Smith family cabin. Built by hand by John Rufus Smith in the late 1800’s. Home to him and Susie Ella Smith and their many children, including my great-grandfather Avery Smith. Home to John Rufe’s son Fred and daughter-in-law Bertha and their children.

|

Every year, I swept you. I sat in you. Sang in you. Repaired you. Photographed you. Marveled at you. And loved you. I loved you so much. You were deep home.

I will always come and rest my hand on your timbers and listen to the wind make your tin roof cry. I will watch you return to the earth. I am grateful for the times I sat inside you. I thank the hands that built you and that built me.

I don’t know where we go from here in the story of the cabin. Will our family organize to bring the timbers out of the wilderness and rebuild a version of the cabin elsewhere? Will we write letters to television programs and try to interest them in rescuing our cabin? Or will we let it return to the earth?

I, for one, will miss walking in the rooms that my ancestors walked. But I will continue to sing their stories and the story of this place.

Thank you for reading, always.

Jeni

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment! The lovely moderator will attend to it gently and promptly.